News

Our stories ... ...

the Netherlands - 03 October, 2024

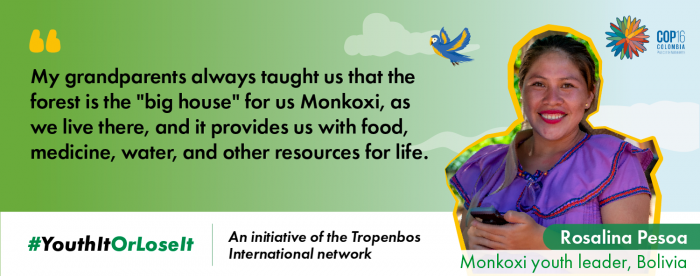

Rosalina Pesoa is a youth leader of the Monkoxi Nation. She is part of Lomerio’s Indigenous Women Organization (OMIML), Comunidad Monterito’s Chief Leader, and partner of the community-based economic organisation OECOM Monterito, which cultivates and transforms Almendra Chiquitana (Chiquitana almond) products.

She promotes women’s entrepreneurial leadership in different economic initiatives that apply local traditional knowledge of using local plants for medicine, beauty, and food. As a community and territorial leader, she has supported her female counterparts in accessing finance for agroecological production in home gardens and infrastructure to adequate conditions for non-timber forest products (NTFP) transformation for accessing massive markets.

Rosalina has also been a key agent of change in the participatory construction of the Monkoxi identity brand to distinguish Lomerio’s products, revaluing ancestral knowledge and local skills.

Rosalina will be part of the COP 16 Event: Youth it or lose it! Traditional knowledge transmission for the sustainable use and conservation of biodiversity this October, 24th in Cali, Colombia. Get to know her through this interview.

What motivated you to become a youth leader in your community? and what activities related to the protection and sustainable use of biodiversity do you carry out?

I enjoy working with society, especially with women and young people. I am motivated to work collectively for my community. I am interested in life as a community in our territory because it is a quieter place where one can be freer than in the city. Knowing my land, knowing the people, and being responsible is what keeps me going as a leader. In my community, Monterito, we carry out several activities to protect biodiversity, such as:

We care for degraded areas by reforesting with the Chiquitano almond tree, which is important to us because it provides various products and economic resources.

We manage forest areas under a sustainable Forest Management Plan, and we are working towards getting green certification.

We protect springs and streams by banning deforestation and burning in the surrounding areas. We also raise awareness within the community to avoid polluting or poisoning the water.

Through the women’s organisation OMIML, we work on creating agroecological family gardens, using only natural fertilisers, without any toxins or chemicals. We (women) are also preparing to be fire spot monitors to reduce the risk of forest fires.

From the stories you have heard from the elders in your community, how do they explain the importance of protecting the forests and ecosystems in your territories?

My grandparents always taught us that the forest is the "big house" for us Monkoxi, as we live there, and it provides us with food, medicine, water, and other resources for life. Since it’s everyone's home, we must care for and love it. The big house belongs to everyone—people, animals, and plants. When my grandparents entered the forest, they always took their tobacco (charuto) and asked permission from the forest's guardian. Animals and trees have their own guardians.

My father used to say that the forest guardian was the hill, and they would ask the hill for permission. This was important because it showed respect; we couldn’t just take everything. We could only take what was necessary for each of us. They also taught us to care for water—we couldn't bathe in rivers or ponds with chemicals like detergent because the Jichi, guardian of water, would leave and the water would dry up.

Nowadays, people from outside deforest their forests, dry out the land, and poison the water, all to take more than they need. This mentality needs to change.

What are the main environmental challenges your community is facing? and how do you think the traditional knowledge of the elders can help overcome them?

The main challenge in my community is drought—we suffer from water shortages for most of the year. We have only one water reservoir, which is no longer enough for animals and irrigation. We can’t predict when it will rain to refill it because the seasons are changing due to climate change.One lesson from our grandparents is to keep our surroundings clean. Everything we needed came from our fields (chacos), not from shops—there were no plastics, bottles, or other pollutants. Even now, we don’t throw away plastics. We organise community clean-ups mingas (another ancestral practice, which consists of collective work for the benefit of the community), to protect the vegetation around the water, care for the environment, and carry out controlled burns. Since the elders have always preserved the forest and have practical knowledge of its protection, we must work together to find solutions.

Why do you think it is important to share your story about your relationship with biodiversity and the ancestral knowledge of the elders in your community at an event like COP16?

I think it is important to share the story of the Monkoxi people because we are taking care of the environment. But what's the point of taking care of biodiversity if other countries are deforesting, polluting and not looking after it? This is everyone's task. Climate change affects everyone globally.

Indigenous peoples have been protecting and preserving biodiversity for years, but I wonder: what's the point if other countries don't do the same?

Events like COP16 are useful to share these experiences, discuss the reality we live in, and demand that other countries fulfill their responsibilities. Without spaces like the COP, the effort that Indigenous peoples make to care for the environment, our “big house,” could not be recognized.

Finally, if you could make a recommendation to an organisation like Tropenbos International or a similar one. What would you suggest they do so that young people feel more rooted in their territories and committed to protecting and conserving biodiversity?

We suggest they support us with productive projects for young people, creating job opportunities so that they can stay in their territories. Projects that help secure food, as crops are failing due to drought. Young people prefer to leave because there are no jobs or educational opportunities. There are no institutes to provide training. They can continue raising awareness about climate change and environmental care, as well as implementing nature-based solutions in Indigenous territories. The key to fostering connection is ensuring we can live with dignity in our own land. If our land provides everything we need again, we will stay committed to protecting it. If it doesn’t, we will abandon it.